|

| austinchronicle.com |

By ALEX CREVAR Published: May 17, 2013 New York Times

I expected my juke joint pilgrimage to feel like a peripatetic wake. Decades ago, blues luminaries like Charley Patton, Robert Johnson and Sonny Boy Williamson traveled across the South, guitar or harmonica in hand, from joint to joint for just enough money and food to get to the next one. In doing so they laid the foundation for nearly every form of popular American music that would follow.

But today, juke joints, once too numerous to count, have slipped away as their owners pass on. When I asked Roger Stolle, a founder of the Juke Joint Festival, held annually in Clarksdale, Miss., how many such places still exist, he replied: “With actual real, live blues music at least sporadically? Maybe five.”

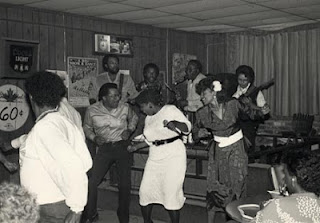

Taking a route through Alabama, Mississippi and Louisiana, I set out to find some of these spots and discovered that where juke joints still exist jubilance remains. Traditionally seen as dens of the devil’s music — jook is believed to originate from an African-derived Gullah word meaning disorderly — the surviving joints have become redefined as sanctuaries. Within their ramshackle walls, a sense of community and a love of soul-searching rhythms reign supreme.

On a crisp April day, I drove from Birmingham to Bessemer, about 20 minutes to the southwest. As I parked at Gip’s Place, a sprawl of do-it-yourself structures literally on the other side of the tracks, a car pulled beside me and a clearly relieved man in a fedora stepped out. “GPS doesn’t do much for you here, does it?” he said. “This place almost has to find you.” (And it could, until recently. The Bessemer city government has just shut down the club, citing permit and zoning violations; at press time, the two sides hadn’t resolved the issue.)

While some other jukes have turned to D.J.’s, Gip’s, opened in 1952, offers only live music. Performers like T-Model Ford and Bobby Rush have played on the plywood stage, housed in a festive space about the size of a living room. When the dance floor heaves, the spot’s namesake, Henry Gipson — he gives his age as “between 80 and 100” and owns a cemetery, where he digs graves by day — takes his position at the stage’s edge, clapping his huge, weathered hands and shouting encouragement.

“The soul and spirit of Mr. Gip and his knowledge and memory of where the blues come from is what you feel here,” said Debbie Bond, a 30-year veteran of the Alabama blues scene and leader of that night’s band, Debbie Bond and the TruDats.

Fueled by the drained invigoration that follows a night “out jukin’,” the next day I drove southwest to Teddy’s Juke Joint in Zachary, La., just north of Baton Rouge. After seeking out Lloyd Johnson Jr., a k a Teddy, I asked him where he was born; the 67-year-old pointed toward the stage, where he said a bed once sat. As a guitar player began fingerpicking, patrons filed in amid mismatched booths and tables, a disco ball, Mardi Gras beads and a sign that read “Welcome: All Sizes, All Colors ...All People.”

“You’ve got to have the want, the love, the upkeep, the will, and the desire to keep it going,” said Mr. Johnson, perched at the bar. “After these are gone, children aren’t going to have any idea what a juke joint was. It’s important because it is the culture of America.”

The next morning, I traveled north through the alluvial plain wedged between the Mississippi and Yazoo Rivers — to some the true home of the blues, having produced stalwarts like Muddy Waters, Elmore James and B. B. King. Today, their legacy forms the skeleton of the region’s tourism draw, and its backbone is Highway 61, known as the Blues Highway.

Juke aficionados from around the world seek out Po’ Monkey’s in Merigold, Miss., just off 61, open Thursdays only. The owner, Willie Seaberry, 73 — he responds to either Po’ or Monkey — has run the joint since he was 16. During the day, he still farms the fields that surround the building, an Escher-like layering of tin, bricks and rough-hewed planks.

“There used to be juke joints all around here,” Mr. Seaberry said as we stood outside, watching the sun set. “Well, a lot of young folks didn’t know how to act, and they just had to close them down.” He looked out across an infinite Delta horizon. “But all my people like the blues.”

At dusk, we followed his people into the joint for $3 canned beers under black-plastic ceilings adorned with a sea of stuffed monkeys and Christmas lights. As the D.J. found his groove with a soul number by the band Chairmen of the Board, a group of regulars arrived, tilting the crowd from majority white to black. Strangers sat at community tables and danced with one another’s dates; the clubhouse mood never changed.

“Po’ Monkey’s is like what the Delta is at its best,” Will Jacks, a photographer from nearby Cleveland, Miss., told me. “It’s more than just a place to have some beer and relax for a night. There’s this magic that happens between people.”

If the Delta is the body of the blues, Clarksdale, 30 minutes north of Merigold along the Sunflower River, is the heart. Markers pay homage to hometown heroes like John Lee Hooker, Ike Turner and Sam Cooke. And this town of 18,000 is the site of the famous“crossroads,” where Highways 61 and 49 meet and where Robert Johnson legendarily sold his soul.

It was the eve of the 10th Juke Joint Festival, and Clarksdale was already humming with the string-bending melodies of impromptu curbside performances. Hundreds of blues fans milled about with their programs to locate the fest’s various music locations. About 7,000 fans would eventually descend on the compact grid of streets to witness longtime bluesmen — some in their 70s and 80s — as well as a new generation of standard-bearers.

The next day, evidence of Clarksdale’s singular focus was everywhere. At one end of town, on the grassy front quad of the Delta Blues Museum, teenagers, college students and families lounged in the sun and listened to live bands. In the town’s center, the esteemed guitarist and singer Robert (Wolfman) Belfour, 72, in a three-piece suit and Panama hat, was finishing a set. Across the street, Marcus Cartwright Jr., 19, who goes by Mookie, also wearing a Panama hat, sat on an amp on the sidewalk and drew bigger crowds with every old-school song he played.

“One of the concepts of the Juke Joint Festival is to highlight the fact that we have these incredible venues that really only exist in one part of the world,” Mr. Stolle said. He is apparently bullish on the state of the festival: next year’s is already scheduled for April 10 to 13. “It gives you that whole sense of the fact that it’s not just a genre of music — it’s a living, breathing culture that happens to have a voice.”

The most obvious bricks-and-mortar example of that commitment to redirect the juke-joint-culture trajectory is the Ground Zero Blues Club. The relative newcomer of the group, it was opened in 2001 by the actor Morgan Freeman and Bill Luckett, a local lawyer, in a converted cotton warehouse, with all the gritty trappings of a great juke: graffitied walls, strings of lights and a down-home front porch with couches. Live acts perform Wednesday to Saturday.

But if you ask musicians and locals to name the best joint in town to experience music, nearly all will send you to Red’s Lounge, which stages blues-only acts Friday to Sunday, run by the beloved and cantankerous Red Paden, 60, a juke owner for 40 years. Inside, space is tight, the ceiling low, and the music as well connected to the original bluesmen as the room’s red-neon glow is seductive.

I’d saved Red’s for last. Apparently so had everyone else — the place was packed. Seated in a folding chair on the floor-level stage, Mr. Belfour moaned, tapped his foot and played his twangy country-blues style — proving why the blues and juke joints are not yet ready for a museum’s glass case.

Hours later — around 2 a.m., as the night’s last band was winding down — Mr. Paden came out from behind the bar, waving his arms through the haze of cigarette smoke and alcohol-fueled revelry. “That’s it, everybody,” he said. “I’m tired.”

IF YOU GO

Gip’s Place, 3101 Avenue C, Bessemer, Ala. Band donation, $10. (Call before visiting.)

Teddy’s Juke Joint, 17001 Old Scenic Highway, Zachary, La; teddysjukejoint.com. Cover on weekends, $10 to $20.

Po’ Monkey’s, Poor Monkey Road, Merigold, Miss. Cover, $5.

Juke Joint Festival, Clarksdale, Miss. jukejointfestival.com. Admission, $15.

Delta Blues Museum, 1 Blues Alley, Clarksdale; deltabluesmuseum.org. Admission, $7.

Ground Zero Blues Club, 352 Delta Avenue, Clarksdale;groundzerobluesclubmusic.com. Cover, $3 to $10.

Red’s Lounge, 395 Sunflower Avenue, Clarksdale. Cover, $7.

No comments:

Post a Comment